The Art of Remembering: Stories We Tell and Shadows We Keep

Memory as truth, nostalgia, and the narratives we create.

On the bathroom counter of my home in San Miguel de Allende, rests a handmade ceramic shell sculpture, its lopsided and imperfect form bearing telltale signs of a child’s creative earnestness. I made it when I was nine—inspired by my mother’s love of seashells, soft white and pink reminders of her Florida childhood. They’ve always lived in our bathrooms—something to the association of being near water, which never made sense to me. But I knew she loved them.

That affection was reinforced each holiday when she and her sister, my aunt, would save the “best gifts” for last, opening them late in the evening, tipsy off food or wine or laughter, those last two presents under the tree. Every year the same—two sisters and best friends exchanging the most bizarre shell art creatures they could find. Choruses of frogs made of clam shells, singing. Motorcycles composed of sea urchin wheels. Cockles, conch, junonia, lightning whelk, wentletrap, scallop, spiny jewelbox, and jingle shells crafted into bodies and scenes complete only with paste-on googly eyes.

The tradition continued for close to two decades, its later years fueled by re-gifting the oldest, strangest ones to each other again and again, unwrapping them in front of the family as we burst out in upriorious laughter. At some point the gift exchanges ceased; kids were grown, family holidays sparse, but the presence of shells continued.

Even now, inside this home in the high desert nestled in a Mexican mountain range, there are shells displayed in all three bathrooms. The shells are more than objects; they are fragments of another life, markers of continuity and escape. As a child, I wanted to add to her collection, to create something worthy of those soft echoes of the sea.The art class kiln wasn’t kind to my creation. The glaze didn’t shimmer as I’d hoped, and the shape leaned awkwardly to one side, but my mother has kept it on display for nearly 40 years, treating it as though it belongs among her treasures.

Even now, when I look at it, I hear the imagined waves I once believed it could hold—a reminder of my quiet hope that making something beautiful could transport us, in our hearts and minds, to to seaside. The shell not just an object of beauty, but one of escape—an artifact of memory, imbued with meaning but also ambiguity. Even now, I ask: Did my mother love it for its craftsmanship, or for the way it symbolized my love for her?

Am I remembering it all now as it was, or as I want it to be?

And in asking that question, I’m reminded of Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red with its exploration of memory as fragmentary, something we build from pieces and perspectives. Carson writes, “Memory is a kind of accomplishment, a sort of renewal even though it doesn’t involve any new facts.” Memory isn’t about accuracy; it’s about meaning. It’s about what we need to remember to make sense of ourselves.

Memory, like Carson’s lyric storytelling, is less a linear account and more a mosaic—a medium shaped by time, intention, and the stories we tell ourselves. The ceramic shell has become part of that mosaic for me, holding truths I’ve created as much as truths I’ve lived.

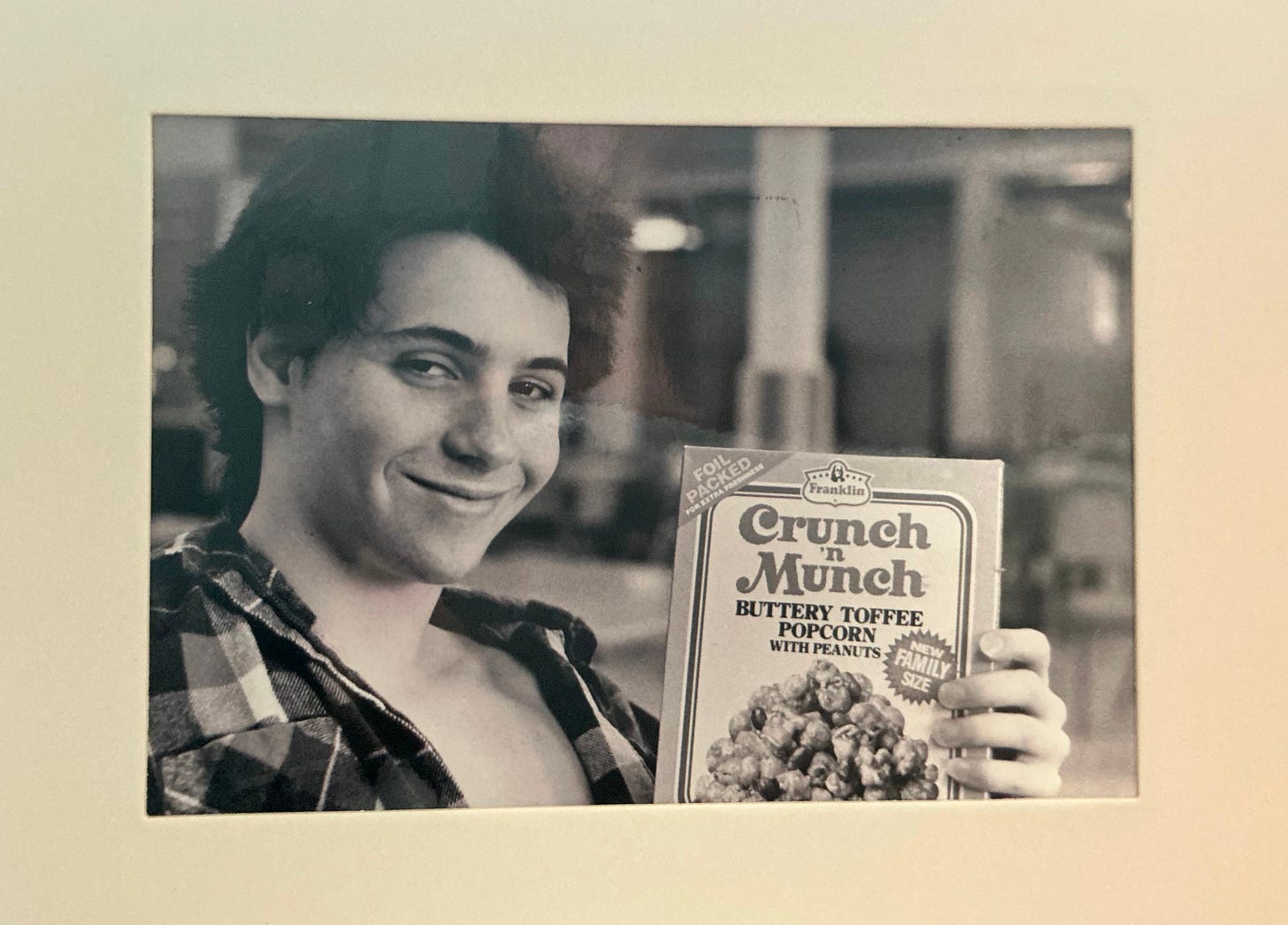

A similar interplay of memory and interpretation emerges in a photo of my brother Judah that hangs in my office. It’s a candid shot from the mid-1980s: he’s grinning wide, holding a box of Crunch and Munch, his freckled face lit up with youthful exuberance. His hair, wild and free, hints at the rebelliousness that defined so much of him. What the photo doesn’t show is where it was taken—Maclaren, a youth detention center where we visited him every Sunday. Nor does it show the ache of his absence or the knot of anxiety turned ulcers that lived in my stomach for years as we adjusted to this absentee rhythm.

To see that photo now is to wrestle with two truths. Judah’s smile radiates joy, a moment of levity and connection, but the context frames it in shadow. I want to remember him this way: carefree, playful, his gaze free from the weight of those walls. Yet the photo is weighted in the losses we couldn’t undo—the devastating isolation he felt in those early teen years, and the holes his absence dug into our family. It is a memory split down the middle, hope and grief.

What does it mean to remember someone fully? Is it even possible? Suddenly I’m thrust into Memento, Christopher Nolan’s breakout film that underscores how memory is often unreliable—a reconstruction we create to make sense of ourselves. The film’s protagonist, Leonard, pieces together fragments of his life through photographs and notes, tattooing bits of truth onto his skin, afraid they’ll slip away—clinging to these artifacts as anchors in an otherwise disjointed world. “Remember Sammy Jankis,” his arm reads—a reminder, a warning, a mantra. But even these tangible markers are susceptible to manipulation, to false narratives imposed by others or by himself.

If I were to tattoo my brother’s essence onto my own skin, what would it say? Perhaps just his name: Judah, or his middle name, Shalom, a call for peace. Or maybe something more ephemeral that reminds me of the way his laugh filled a room or his hand on my shoulder, steadying me when I stumbled. Judah’s photo, like Leonard’s Polaroids, holds both the beauty of what was and the vulnerability of I wish had been—what I could alter, edit, create, and return to.

The truth of my brother’s life is fragmented, contradictory. He was both gentle and volatile, a protector and a destroyer, a boy who dreamed of freedom and a man who couldn’t escape his own shadows. I hold all these truths in tension, not because they make sense, but because they make him whole.

There’s a summer from my childhood I often reshape in the telling. We had moved to a new town when I was ten, and the railroad tracks behind our house became my sanctuary. I spent those months tracing trails, mapping the new town in a notebook, and sitting by a small pond where light filtered through the trees in golden ribbons where I’d toss rocks and watch the chartreuse algae separate, making way, in moments, for the dark water below. It sounds idyllic, and in some ways, it was. But the tracks were also refuge, a place where I could disappear from a stress-filled home and the overwhelming strangeness of a new school and new set of social dynamics I didn’t yet know how to navigate.

When I talk about that summer now, I focus on the wonder of it—the enchantment of discovering nature, the freedom of solitude and independence. I omit the desparate loneliness, the way those hours served as a shield against my shyness and fear of rejection. This rewriting, a way of holding onto the parts of the story that let me see beauty in what was also a time of struggle. As Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola suggest in Tell It Slant, we write not to report but to reveal, selecting moments and images that illuminate larger truths. The railroad track adventures, in their duality, are both a site of hiding and a space of discovery—a metaphor for memory itself, where light and shadow coexist.

The ceramic shell, Judah’s photo, the summer by the railroad tracks—these artifacts of memory are more than fragments of the past. They are collaborations, shaped by the selves I’ve been and the self I am now, between the truth of experience and the narrative lens through which I view it. Memory, as Anne Carson suggests, is a kind of renewal, a place where fact and feeling intermingle. In shaping these stories, I’m not distorting them but allowing them to evolve, holding both the clarity of what was and the possibility of what could be.

Memory isn’t a perfect record. It’s a negotiation with the past, a way of reckoning with the shadows and the silences while finding meaning in what remains. Judah’s photo doesn’t explain the sharp edges of his life or fill the gaps of his absence. The ceramic shell doesn’t carry the waves I imagined as a child. Yet both anchor me to something real—something worth holding, even in its incompleteness.

As Miller and Paola suggest in Tell It Slant, storytelling is not about reporting events but revealing truths. We shape narratives not just to remember but to make meaning, to illuminate the contradictions and ambiguities that memory can never fully resolve. Judah’s life, like all lives, was a tangle of gentleness and chaos, hope and heartbreak. To remember him fully is to embrace all of it—not because it’s neat or complete, but because it’s true.

The shadows in memory, those spaces between what we know and what we long to understand, are where imagination lives. They are where I let myself wonder who Judah might have become if his story had continued, where I allow space for the questions that have no answers. What would peace have looked like for him? What might he have taught me, or himself, had he lived past twenty-eight? These questions are not meant to resolve his story but to carry it forward.

To remember is to curate, to shape, to hold. It is an act of love, of resilience, of becoming. The stories we tell ourselves are not simply about the past—they hold who we are now and who we are still evolving to be. And so I return to the archive, to the fragments and the shadows, not for resolution but for connection.

Because in the end, it’s not about what we remember. It’s about how we remember. And that, I think, is where the story begins.

This is so lovely and so profound, I think Hunter. My own memoir, Turning Inside Out is indeed the creation of a story, as you say, coming out of events in my life, and crafted in a way that makes sense, makes meaning. It is a meaning that led to my creating my two podcasts on WW II Baby Substack, a meaning that, as Victor Frankl says, I am creating as I respond to the opportunities and challenges that life puts in front of me.